Art as Relationship: Should AI Count?

A critical look at AI’s expanding role in image-making and whether it weakens the trust and connection between artists and their audiences

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

02 Dec, 2025

Sometimes, I wonder how good of a job I’ve done over the years of fooling my readers. I’ll have succeeded if you’re surprised to learn that I must fight the constant inclination to become a true Luddite. I’ve come to appreciate change over the years – but adaptability for me is the product of experience rather than nature. As such, I take great pains to check myself before weighing in on any new technology, especially those I worry are more sensationalized than stabilized. This instinct has been the death of my social media presence, but I’ll admit it’s generally been good for business.

Still, the more entrenched I become in the world around me (the sorry side effect of my meager mid-twenties investing debut into the S&P 500), the more I start to wonder if maybe I try a little too hard to see all sides of every issue. As I watch the news, I find myself coming again and again to the words of Mother Teresa: “We belong to each other.” With every passing day, every protest, every trial, every unprecedented tragedy, an ancient truth seems to present itself more vividly: The actions we take individually will have an impact on others. While we may not be able to predict exactly how, our best bet is probably to try to live as well as we can.

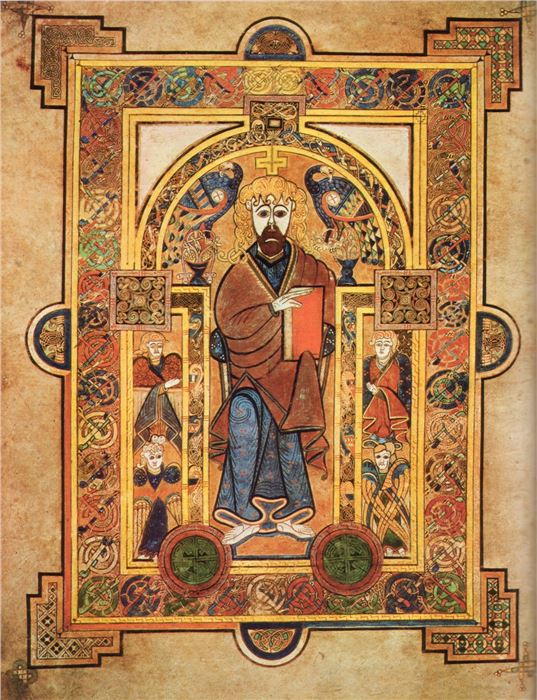

Christ Enthroned, from the Book of Kells, 9th c.

Nowhere, perhaps, is this more immediately obvious to the average Westerner than in the slow degradation of the Internet. Many sources report that, as of 2025, bots now account for over half of Internet traffic – and AI-generated media is poised to take over a significant portion of the human half. It’s little wonder we’re experiencing crises of loneliness and misinformation. With every choice to pass off the artificial as the human, with every effort to legitimize its creation as akin to human effort, we deepen the isolated echo chamber into which each of us is increasingly cast.

Here is where I fight again the little Luddite in my brain. I am not against AI; in fact, I’ve found ChatGPT to be an excellent source to assist me in several areas of my life – freelance business strategy, health and fitness, car shopping, collations of Reddit posts to navigate delicate interpersonal affairs. I still talk to my dad about all these things, of course; he’s been my advisor from the beginning. But he’s as relieved as me to find an outlet for some of the lower-level questions that pop up in my day-to-day. I’ll even occasionally break it out to draft a report, proposal, or overview – though I’ve found the fact-checking required often offsets any time savings past the preliminary phase.

But the one area I have not been able to abide, try as I might, is so-called “AI art.” And I’ve really tried. I’ve trawled the forums, tried gazing into the soulless eyes of the glazed, smiling figures, even drafted a few quick prompts here and there. But the arguments ring as hollow as the pieces themselves. “Artists are gatekeeping creativity,” they say. Yet they have little interest in understanding the vast amounts of hidden skill and technique that underpin any true craft. AI may have its uses – say, for simple Photoshopping in marketing collateral – but it is a tool, not a medium. “AI is pushing artistic boundaries, just like the computer,” they argue. Yet they ignore the vast difference between a digital artist’s control with her tablet and an “AI artist’s” dissociation from her final product. “Prompting is a skill,” they observe. But there are countless kinds of skill; many have nothing to do with art. There is no reason to co-opt an existing term to describe AI prompting, especially not one so rich with truly human history and significance.

.jpg)

Detail of The Dome of the Rock (photo by Leon petrosyan, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Art is not made of communication; art is communication. Art is a relationship between artist and viewer; “AI art” is a conversation with an algorithm. Artificial intelligence adds an additional level of artifice to an image that serves only to obscure each of us from each other. Despite its legitimate uses, to pass it off as “art” – as the work of human hands – is, no matter how I look at it, to reject the relationship between artist and viewer. It is to suggest, however subtly or unintentionally, that what is deepest about the human experience, what binds us each to each other, is at its core so meaningless that the simulacrum is as valuable as the thing itself. It is to degrade our shared hunger for connection to a commodity, a hobby, an experiment.

I believe many of us experience this guttural sense of rejection whenever we see an AI image. I can hardly spend five minutes on Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube without someone calling out “AI slop” or applauding a creator who supports “real artists.” Even many highly innovative art communities online reject AI output categorically. We’ve even seen a (slightly disturbing) resurgence in pseudo-racist terminology to demean anything that so much as whiffs of machine learning. I am heartened by the intensity and consistency of this response. At the same time, I do feel for those who are genuinely excited about discovering new applications for this exciting new technology. In pushing back against the increasing sense of digital isolation, it seems the online community is pushing some AI enthusiasts closer to the fringes.

J.M.W. Turner, Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth, 1842

J.M.W. Turner, Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth, 1842

Like many debates, this may come down to a simple case of equivocation. Artists – those perhaps best poised to speak on the nature of their work – define art in so many ways that it’s difficult to settle on one. But all seem to agree that, to some extent, their work is meant to convey something to the viewer, even if at the extreme it comes across as an absence of meaning. Whether one holds a sort of “death of the artist” stance or believes art is merely a conduit for moral education, the debate hinges on some relationship between art, artist, and viewer. These three elements interweave in myriad ways, but the relationship itself is a sort of sacred truth at the foundation of the craft.

It is possible that there could be a way to integrate artificial intelligence in the image-making process in a way that does not disturb this relationship. But as it currently stands, most AI practitioners seem unable to create works that can engage meaningfully with all three parties. The artist is often unrecognizable; the art, plagiarized; the viewer, alienated. (We haven’t even touched on the ethical implications of art theft to train these LLMs!) If such an image is disclosed to be AI-generated, it is an interesting thought experiment. If it isn’t, it is a betrayal of a deeply human trust. With each betrayal, we drift further and further apart in our small, online bubbles, and the Internet becomes an even less hospitable place. When they masquerade as art, AI images have a tendency to become its very antithesis.

.jpg)

Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504 (photo by Livioandronico2013, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I have little doubt that AI is here to stay. I have some doubt that there will ever be an “artist” who can convincingly rely on artificial intelligence alone to enter the historical canon. I am willing to be proven wrong, but as far as I’m concerned, I haven’t been yet. I am grateful for the many ways in which it is revolutionizing the experience of working and learning. Its role may be expanding, but that doesn't mean it shouldn’t be defined. Our shared communities depend on it. We belong to each other.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page