Friedrich in the Arms of Winter

Caspar David Friedrich’s mystic landscapes, their romantic origins and his revival in 21st-century exhibitions

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

05 Dec, 2025

North – where the tight cramp of winter night cuts hard into the span of each day’s light, and long-handed shadows scrape shapes across the frigid land, where sublime and lethal beauty linger in the pale colors of mid-morning dawn, in the low swoop of the sun’s arc through the dark sky and its vanishing dip behind black and leafless trees. Here is Thule, the legend and land of lost Pytheas the Greek, who wandered the North and the sea in search of the source of amber and found instead the thick salted ocean freezing into ice and steaming under the weight of fog piled over the edge of the world. Here is the monstrous land of ancient Vikings, gods who cut holes through mountains for their passion and pleasure and Thor hammering lightning from the sky with mighty Mjölnir, and the cavalcade of the living and the dead passing almost as one behind Odin’s Valkyrie. Mysteries and magic happen here, where rational thought never crushed the blue and jeweled truths of pagan light and half-light. North – into the imagined lands of Caspar David Friedrich.

Caspar David Friedrich, Felsenlandschaft im Elbsandsteingebirge (Rocky Ravine in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains), Oil on canvas, 37" x 29.1", 1822

Friedrich was thirty-one when the revolutionary army of imperial Napoleon defeated Prussia in 1806. The French occupied Germany by the end of the decade, and although the war of independence to eliminate the invaders ended in victory in 1814, even this triumph turned to disappointment when the victors were forced to allow a loosely allied collection of states to survive like an echo of the feudal past and failed to create a united nation. Patriots who had sacrificed life, health, and liberty in the fight for German freedom found themselves in a weak confederacy which was not granted self-determination, as the mapped land became a playground for the great powers of Austria, Great Britain, Russia, Prussia, and France, whose struggles for global dominance overruled the interests of German citizens. Early 19th-century liberal and nationalist movements alike were crushed by the Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich who introduced the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819, censoring the press, controlling the academy, and forbidding political organizations. The land was beautiful, but a dark spirit dwelled over it.

Caspar David Friedrich, Cairn in Snow, Oil on canvas, 24" x 31.4", 1807

Caspar David Friedrich, Cairn in Snow, Oil on canvas, 24" x 31.4", 1807

Patriotic and liberal Germans retreated to an imaged world, seeking the heart of their culture under oppression. Wilhelm Richard Wagner and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe provided it. Friedrich followed. Goethe’s The First Walpurgisnacht imagined singing druids climbing the mountains to celebrate the Allfather Odin with Spring fire at Beltane, the ancient Mayday festival. The druids were warned by an onlooker that their old religion was forbidden by the Christian conquerors, who had slaughtered their wives and children, but they carried on regardless, quietly gathering their stacked firewood during the day, posting a silent guard of men throughout the woods, and declaring “the forest is free!” And at night, when their fire burned and Odin’s spirit moved among them, the flames were purified of the smoke and good Christians trembled, believing that their devil was abroad in the wild singing they heard and the fire they saw raised upon the heights.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood, Oil on canvas, 43.4" x 67.3" 1809 - 1810

Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood, Oil on canvas, 43.4" x 67.3" 1809 - 1810

The first part of Goethe’s Faust was published in 1808 – its heady blend of mystical power invoked by people working the indigenous and ancestral magic of the pre-Roman incursion appealed to receptive Germans suffering under the burden of blood and occupation. Faust was hungry for knowledge, for self-realization at any price. Freedom! The land was supernatural. The great forests were alien environments to foreign intruders. The nation’s mountains were host to liminal pagan rites – like the druids of The First Walpurgisnacht, Faust’s ancient festival of fire and fertility was held on the mountaintop, but now the location was specific: it was on the Brocken, the highest of the Harz Mountains in the misty heart of Germany where the hot fires of ancient faith burned brightest. These romantic symbols of German liberalism and proud nationalism filled Friedrich’s paintings.

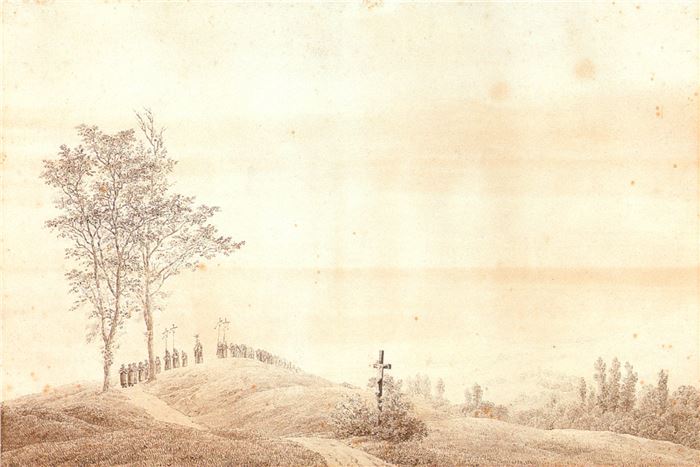

Caspar David Friedrich, Pilgerzug bei Sonnenuntergang, Procession at Dawn / Dusk, Pencil and Sepia on paper, 16.02" x 24", 1805

Caspar David Friedrich, Pilgerzug bei Sonnenuntergang, Procession at Dawn / Dusk, Pencil and Sepia on paper, 16.02" x 24", 1805

But Goethe’s Gothic presence in the German imagination also invoked a different kind of darkness – a darkness that allowed the living to enter the domain of the dead and return after wandering through the veiled lands of half-life. The people inhabiting Friedrich’s fantasies of the Northern landscapes of the Baltic coast and the Harz Mountains turned their backs on their doubled audience – rejecting both us and the artist and preferring to face a hostile and frightening world alienated and alone, to leave us to our contemplation. Friedrich had good reasons to paint them immersed in isolation, and good reasons to paint the desolate mood and miasma that hovered over the landscape in the mirror he held to his country. Under Napoleonic occupation, Germans were like ghosts living a vague opium vision, living like the dead, like revenants, like the dreaming procession of spectral monks in Friedrich’s Procession, which won him a prize from Goethe in 1805.

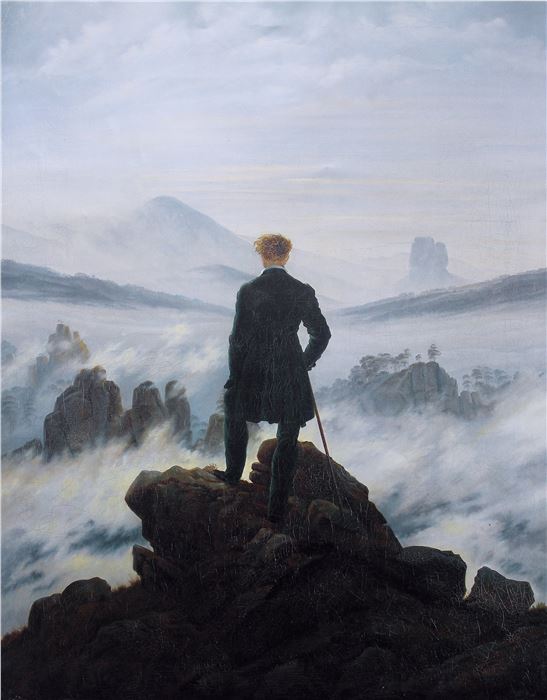

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the sea of fog, Oil on Canvas, 38.5 x 29.1", 1817

The long gaze of the opium aesthetic was potently embodied in the slow mood and melodrama of Friedrich’s Gothic landscapes. There is no direct evidence that he was a laudanum drinker, but in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries taking a liking to a little laudanum was as common and unremarkable as swallowing a soothing aspirin. His 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog was a perfect illustration of an opium-eater’s disposition, with the self-contained and romantic figure caught in a Kantian reverie as he gazed over the sublime landscape, his moody mind steady and superior to infinite nature, a tragic and solitary hero poised in the calm and confidence of his thought yet isolated by his lofty witness, like De Quincey gazing timelessly over the London night in his Confessions. De Quincey had read Kant while on laudanum, and he thought he understood the abstruse thinker – whether he did or did not was of no consequence, for even by describing his drug-aided powers of perception he had set a fantastic archetype for a new kind of educated and philosophical bohemian, self-possessed and intellectually expanded by the influence of opium and both set apart from and aloof to the ordinary concerns of day and life. It was an attractive archetype for young people dealing with the horrors of the Napoleonic era. De Quincey discovered he had the power to generate and direct waking visions while under the weight of opium, and this short cut to creativity became an alluring temptation to youth, offering, “a power of painting, as it were, upon the darkness, all sorts of phantoms…” which he compared to a theatre presenting nightly spectacles “of more than earthly splendor.”

Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice, 1823–24. © Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk Photo by Elke Walford. Courtesy of Hamburger Kunsthalle

Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice, 1823–24. © Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk Photo by Elke Walford. Courtesy of Hamburger Kunsthalle

Following the cycle of the slow seasons of history, Friedrich experienced a popular revival in 2025, tagged as celebrations of the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of his birth, but probably more realistically to be attributed to the renewal of his relevance to the social situation in Germany, which is again unsettled by its collapsing demographic, its immigration policies, and its declining status as the leader of Europe, increasingly supplanted by youthful, invigorated France. In fact, the Friedrich revival began two years earlier, when the Hamburger Kunsthalle opened their superb Caspar David Friedrich: Art for a New Era in the winter of 2023 to record breaking queues of 335,000 visitors. Director Alexander Klar told Hamburg News the largest demographic group were young people aged between twenty and thirty. Friedrich’s triumph in Hamburg was quickly followed by a string of German exhibits in 2024. In Dresden, the Albertinum’s Caspar David Friedrich: Where it all Started, saw 236,000 visitors, breaking the record for attendance as one of the most successful exhibitions in the history of the Dresden State Art Collections. A month before the Alte Nationalgalerie’s Caspar David Friedrich: Infinite Landscapes exhibit ended in Berlin, the gallery reported more than 200,000 visitors, and like the Albertinum extended their opening hours to accommodate demand. The Pomeranian State Museum in Greifswald, a city distinguished as the artist's birthplace, hosted three special exhibitions of his work throughout 2024, and in winter the people of Dresden had a second helping of Friedrich when the Kupferstich-Kabinett hosted Caspar David Friedrich – The Draughtsman. Even the little Schiller Museum in Weimar broke attendance records with their Caspar David Friedrich, Goethe and Romanticism, which was open through Spring of 2025.

.jpg) Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, Oil on Canvas, 13.7" x 17.2", (c. 1825–1830)

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, Oil on Canvas, 13.7" x 17.2", (c. 1825–1830)

Soon Friedrich arrived in New York. In Spring 2025, the Metropolitan Museum opened its Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature, reminding Americans of the power of his paintings and attracting 300,000 visitors. Reacting to an anxious world, Gothic romanticism was back. The cultural mood had suddenly changed. In a post-pandemic world of isolation and anxiety, Friedrich’s opiated atmosphere of alienation resonated – these were paintings of the recurring winter of the West.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page