Women of Pop: From Sister Corita Kent to Rosalyn Drexler

Women in Pop Art expanded the movement with deeper critiques of consumer culture, gender norms, and representation

Kristen Osborne-Bartucca / MutualArt

21 Nov, 2025

Sister Corita Kent, “tiger,” 1965.

Sister Corita Kent, “tiger,” 1965.

For most people, a short list of Pop Art’s luminaries will consist of only men – Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, James Rosenquist. But as with most art movements, the people on the margins – in this case, women – did equally, if not more compelling, work as those securely ensconced in the canon. Women Pop artists both exemplified the tenets of the Pop Art movement, such as its sophisticated but playful experimentation with graphic design, its commentary on mass culture, kitsch, and consumerism, and its interrogation of the meaning and pitfalls of celebrity, as well as offered sometimes subtle, sometimes explicit critiques of how the patriarchal society they lived and worked in often subjected their bodies to minimization, surveillance, and violence. This article will look at the work of a few female Pop artists through those themes.

Mass Culture and Kitsch

Pop artists painted (and sometimes actually incorporated) household items, used mass production techniques and mass media messaging, and, the Guggenheim notes, “took inspiration from advertising, pulp magazines, billboards, movies, television, comic strips, and shop windows.” As with almost anything that takes pop culture as its inspiration and subject, there are degrees of kitschiness, camp, irony, humor, and superficiality. Pop artists both celebrated and critiqued consumer culture, their oft-ironic tone perhaps belied by the sheer pleasure of their colors and shiny surfaces as they transfigurated the mundane into the iconic.

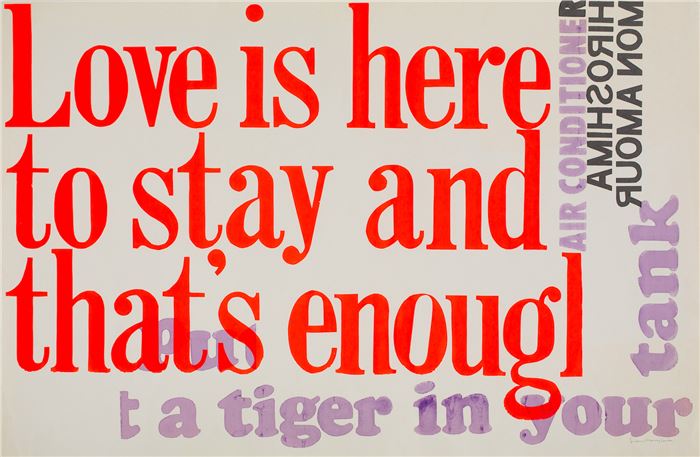

Sister Corita Kent, “enriched,” 1965.

Sister Corita Kent, “enriched,” 1965.

The women artists explored all these styles and ideas, but even a cursory overview of their oeuvres shows that they often offered more in nuance or complexity than the male artists. Sister Corita Kent, who was a sister in the Immaculate Heart of Mary religious order for several decades before leaving it in 1968, was a profoundly talented graphic designer, artist, and activist who incorporated consumer imagery like many Pop artists. "enriched bread", 1965, features the colors and text of the household staple Wonder Bread and "sunkist", 1965, features the slogan “mmmarvelous Sunkist taste!”, but there is more here than mere references to grocery items. The former also has text from Camus about the greatness of mankind, and the latter has verses from Joseph Pintauro, a queer priest, writer, and activist, on the luminous feeling of the wind hitting one’s face on the beach. Kent’s juxtapositions are humorous twists on Proust’s madeleine – a generic grocery item prompting philosophical rumination.

Odd Man In, installation of Dorothy Grebenak’s work at Allan Stone Gallery, 1964.

Odd Man In, installation of Dorothy Grebenak’s work at Allan Stone Gallery, 1964.

Some of Dorothy Grebenak’s works were of consumer goods as well, but the fact that her chosen medium was not painting or silkscreen but thick wool hooked rugs, a traditionally “feminine” and therefore lesser form of artmaking, meant that her work was marginalized by the misogynist gallery and collecting world (a rug featuring a box of Tide, for example, was purchased by collectors and used as an actual rug). She didn’t change her medium, however, and continued to delight in making laborious, handmade pieces that ironically depicted factory-made consumer products (Tide, rotary phones), industrial objects (a ConEd manhole cover), currency (a $2 bill), and mass-distributed “art” (a comic strip alluding to Roy Lichtenstein). Her craft offers a direct response to the conspicuous consumption of the era.

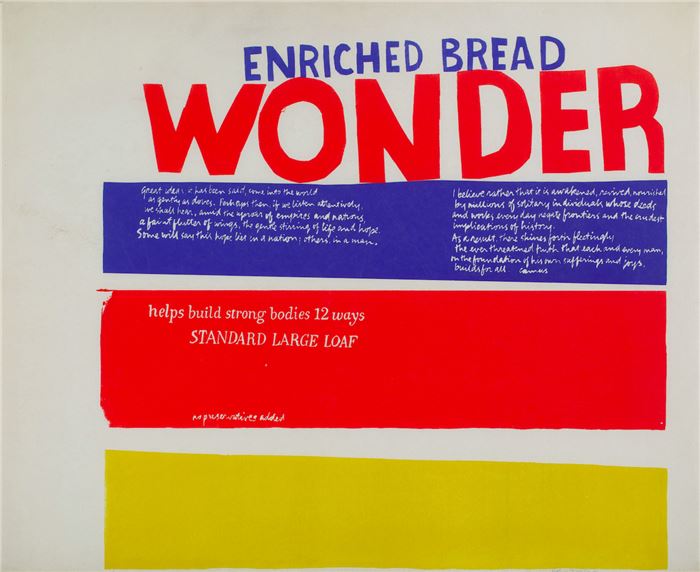

Idelle Weber, Dewey, Ballantine, Bushby, Palmer, 1958.

Idelle Weber, Dewey, Ballantine, Bushby, Palmer, 1958.

Idelle Weber’s black silhouettes set against bright, monochromatic squares of colors are usually of men and women engaged in banal tasks, such as riding an escalator, looking at papers, strolling, and standing. Her gallery, Hollis Taggert, says that “by rendering the figures anonymous, the artist makes them universal: a viewer could occupy any of these roles.” But a large contingent of them are clearly the men in the gray flannel suits of corporate capitalism, and their empty faces connote only empty souls. In Dewey, Ballantine, Bushby, Palmer, 1958, lawyers at the famous firm pose self-importantly with blank sheets of paper. There’s one female secretary there, but she has neither name nor face – an accurate depiction of how women were viewed in these spaces. Three Suits, 1962, is metonymic satire, with the three men of the title gesturing to each other in the void. It’s a Business, 1962, shows another generic man in a suit mindlessly scrawling chalk patterns over and over again on a wall. Weber’s men are Hitchcockian ciphers, Willy Lomans who have lost individuality and interiority.

Celebrity

Rosalyn Drexler, Marilyn Pursued by Death, 1963.

Like their depictions of mass culture, women Pop artists added another dimension to their representations of celebrity. Rosalyn Drexler, who was truly a little bit of everything – a visual artist, a novelist, a critic, a wrestler, a comedy writer, a playwright – did a Marilyn Monroe painting, Marilyn Pursued by Death, 1963, which makes explicit what Warhol only alluded to in his Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962 – that being a scrutinized, stereotyped public figure could be isolating and soul-crushing.

Kiki Kogelnik, Marilyn, 1961.

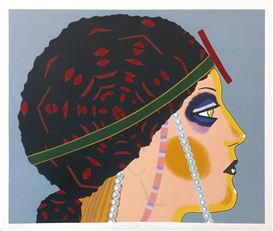

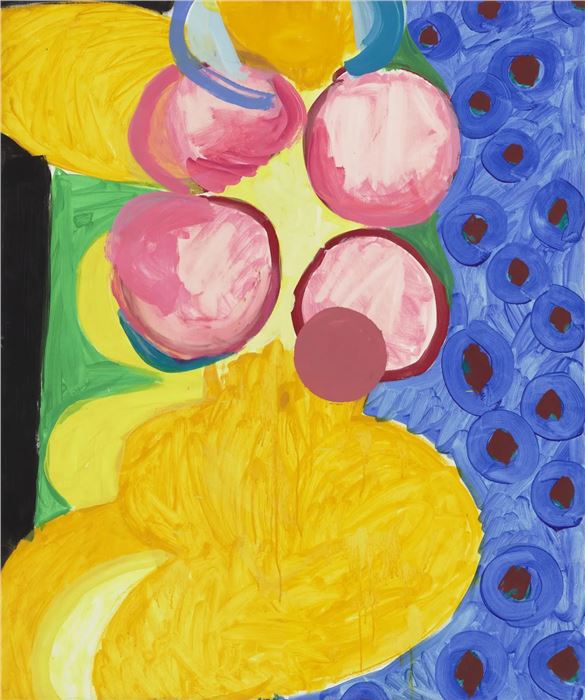

And it might be even more so if that public figure is a woman, apt to be continually sexualized, her value predicated not on her talents or intellect but on her beauty. Kiki Kogelnik’s Marilyn, 1961, is abstract, but the soft, bulbous forms in golden yellow and cotton candy pink are meant to suggest Monroe’s curves. She’s all part-object, pretty but soulless.

Sexuality

Male Pop artists made works featuring women, but, looking to Tom Wesselman in particular, they were usually the “mindless-boob-girlie” symbols (a phrase from the 1970s feminist group Redstockings). Female Pop artists’ subjects could also be provocative, but there was nuance there. First, the simple fact that the artist was a woman depicting a woman changed the works’ interpretation, and second, these artists were apt to make their women subjects, not just objects.

Rosalyn Drexler, Self-Portrait, 1964. (left) Self-Defense, 1962. (right)

Rosalyn Drexler, Self-Portrait, 1964. (left) Self-Defense, 1962. (right)

Weber’s Woman with Jump Rope, 1963, is a black plexiglass silhouette on the wall, but her form is fuller and not overtly sexualized. She’s in the process of jumping over a glowing neon jump rope, also affixed to the wall. The whole image is playful, exhilarating – not seamy or soulless. Drexler’s Self-Portrait, 1964, is sexy and charming, showing the artist lying on the ground and rocking her stocking-and-garter-clad legs up over her head. Her skin is cerulean, the background intense cadmium red, her dress fallen around her head a diaphanous cotton candy pink. She stares straight out at the viewer, her expression one of confidence and a wry knowingness.

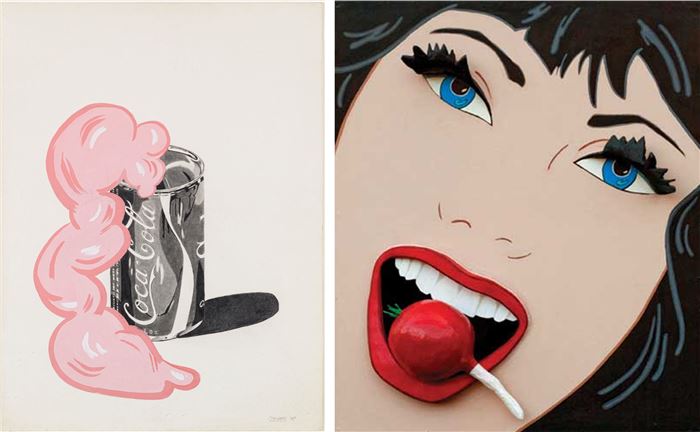

Marjorie Strider refused to let her women remain literally or figuratively two-dimensional. In Girl with Radish, 1963, she paints the woman’s white teeth and red lips playfully biting down on a radish, but the radish and the heavy black lashes are three-dimensional (she called these elements “build-outs”). She did a few triptychs of bikini-clad women, such as Triptych II (Beach Girl), 1963, and Green Triptych, 1963, with the women’s breasts pushing out into the viewer’s space. While they might invite touch, that invitation also confers subtle judgement on viewers’ prurient desires. Come Hither, 1963, is not three-dimensional, but the woman’s knowing smile and penetrating eyes give her a sense of power and autonomy not to be found in Wesselman’s faceless “Great American nudes.”

Life Under Patriarchy

While a patriarchal society values women for their youth, beauty, and their sex appeal, it also surveils and controls, sometimes violently, their sexuality. Drexler has numerous unsettling paintings fusing sex and violence. In Put it This Way, 1963, a man aggressively slaps a woman and her body arcs toward the front of the picture plane. Self-Defense, 1962, is a heaving, powerful scene of a woman pinning a man down on the ground, the two of them fighting over a gun. Her face is contorted in fear and rage, her exposed breast suggesting a thwarted sexual assault. Love and Violence, 1965, is a bright red canvas bifurcated across the center with the bottom scenes showing men fighting and the top showing a grim-visaged man pulling a seated woman’s turned face towards him. Though the image was appropriated from a film poster that did not intend to be hostile, Drexler’s aesthetic choices reveal the nascent violence embedded in all heterosexual relationships.

Marjorie Strider, Party, 1973. (left) Girl with a Radish, 1963. (right)

Marjorie Strider, Party, 1973. (left) Girl with a Radish, 1963. (right)

The women of Pop were certainly of their time and of their movement and should be discussed alongside their male counterparts when considering basic stylistic tenets and themes, but, perhaps because of their marginalized status, they brought a more heightened sense of self-awareness, societal criticism, and a willingness to interrogate traditions and tropes.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page