Identity, Tradition, and the American Experience: Hüicho!

Mixtec heritage, military discipline, and Californian life through ancient patterns and contemporary imagery

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

28 Nov, 2025

There is rich American truth in that blank black dirt scraped onto the rich red canvas, that lush darkness made of loam taken from fertile Californian fields, where Hüicho’s Oaxacan parents nurtured food for Americans to eat, following farm work across scraped border lines. They are Mixtec, the pyramid-building people of the clouds, subtle and solid. Hüicho explained,

My parents migrated up here following the crops. They’re crop people. They always planted, they always sold fruit, vegetables, whatever was the season. That’s who they are. They always tended to the fields. We had dirt literally underneath our fingernails and in our history. It’s always been taught, but not like a course, you live it. You live it and it’s in you and for whatever reason you can’t let go of dirt. I think we all have it. When you’re a kid you go out and play in the mud and get dirty, then later, I guess you don’t, but I still haven’t stopped.

That black dirt is thick. Encrusted. Organic. It is the crude texture of concrete or raw stucco, scoured, and rough, and dried. It is from the belly of the earth. That living blackness as flat as gunpowder before the flame. Hüicho has worked the earth with understanding and studied what his process needs. He explained,

The dirt has been sifted six times, six different sizes, to get fine dirt, cleaning the dirt. And turning it upside down from where it’s at on the floor, putting it on the wall, elevating it. I mix the dirt with retarder and then mix in the paint – it’s ivory black, the blackest black I can find.

Hüicho! The 80s 2, Acrylic, Strontium Aluminate Europium Dysprosium & Dirt on Canvas, 48" x 48"

Hüicho! The 80s 2, Acrylic, Strontium Aluminate Europium Dysprosium & Dirt on Canvas, 48" x 48"

His earth is more than a pigment, then, more than a texture, more than a surface finish. His earth is a symbol. “I’ve always known mud,” he said,

Going to the fields with my parents, it’s all we saw. It’s all you saw when they came back and you had to pull their muddy shoes off. It was always there. The tires, the tracks, they leave that impression, the negative space. On the surface you see it as ugly, but when you look deep into it, it’s beautiful. It’s what I remember.

The paintings are reconciliations of opposites. That smooth red is the blood, the belching lava, the agaric in the alembic. It is from the core. That deep red is the color of life. This is a declaration. Here we are, bright and bloody against the black earth, we are the living, and the dead, the red and the black. This is simple. This is real.

The modern Mixtecas are fine metalworkers, and a thousand years ago their ancestors established the artistic traditions that permeated pre-colonial art in the southern part of the northern continent that became America. Their buildings were intricately decorated with stepped fret patterns called xicalcoliuhqui, precisely arranged in dry stone. These shapes are the patterns Hüicho saw in his grandmother’s lap as she worked embroidered cloths, but the simple, jagged, and hard-edged steps are also the patterns of warrior pride, once decorating the shields of his fighting ancestors before the Spanish colonists came and conquered Mexico. He said his paintings gave him:

…a lot of guidance, and it’s from all my life. I just hadn’t seen it, until I stopped and actually really saw things for what they were. These paintings took me back to my grandma, when she was sewing these patterns on her shirts, and now I’m wondering why was she doing that, and now why am I doing that, and maybe we’re becoming in service to the art, or whatever it is that’s being transmitted. These patterns have existed since the pyramids were made, so it’s obviously something that’s important.

Hüicho! El Comienzo, Acrylic and dirt on canvas, 48" x 48"

Hüicho! El Comienzo, Acrylic and dirt on canvas, 48" x 48"

His ¿Te Acuerdas? (Do you Remember?) allows a Christian cross to rise from a xicalcoliuhqui pattern, questioning the transformation and displacement of ancient traditions under the weight of the new religion of the Spanish invaders who demolished Mixtec buildings, culture, and art.

Because Hüicho is deeply connected to his people’s past, there is a clear danger of adopting the language of patronizing orientalism and woke othering in describing it, but such pretentions would be idiotic in the context of his work. Before painting, Hüicho was a fighter, too, serving in the Iraq war as an E-5 Sergeant / 0331 Infantry Machine Gunner in the United States Marine Corps. He is a patriotic and eagle-tattooed American with an M203 grenade launcher inked into his arm. His military service taught him a deep discipline which matched his upbringing. He commented,

…this is where I’ve been led to after many years of putting in the work, grinding away, just having this mentality of putting your head down and one foot in front of the other, and not stopping. This is a mentality I’ve had since I was young, besides my parents always working hard and never stopping whatever they were doing. I also implemented that in high school, when I wrestled or I did track. It was always grinding away every day, and I still do. Always grinding away, never stopping. There’s no need for anything other than just get to work, and that alone satisfies one part of me. Did you do what you’re supposed to do today? When you grind away, you can answer that question simply as ‘Yes, I did.’

A decade ago, the GI Bill enabled his master’s degree at California State University Northridge and challenged his aesthetics. He was already a gifted figurative painter, and the modernist approach he encountered at the institutional art school, ruled by the approved standards of the US government, was hostile to his training as a representational artist. He used the confrontation to his advantage and began questioning the integrity of his art.

CSUN helped me open out my creative side. It went against the grain of what I wanted to do, but it’s always nice getting that pushback. That’s the whole thing about this painting, too, it’s the pushback. You’ve got to do some pushing, and the world’s going to do some pushback also. You have to do your work, part of it is pushing back. It’s ok. That’s life. Part of life is accepting it, and part of life is living it. Don’t get mad. …Part of this whole thing of making this art is fighting to get to where I’m at. Because I’m always fighting with myself, too, what I want to do, and what I want to say. Because time is precious, you don’t want to waste time on things you don’t want to say, you want to spend time on things you do want to say.

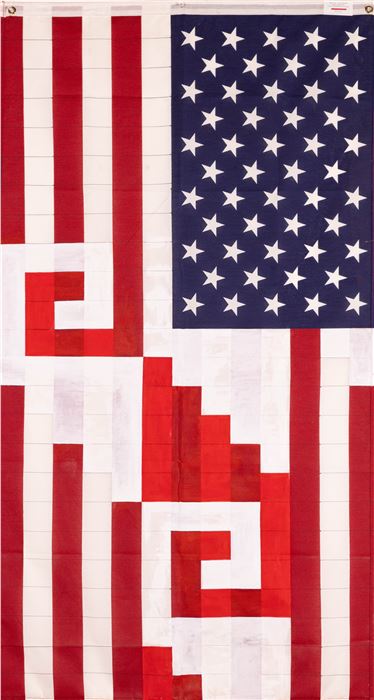

His enthusiasm for his country takes nothing from his deep love for his family’s heritage. Born in Watsonville, California into a large community of Mixteca, and raised in Oxnard, which is known as Little Oaxaca, he is as proud of his flag as he is of his blood, which he shed for his country, and his paintings combine his culture with his truly American life.

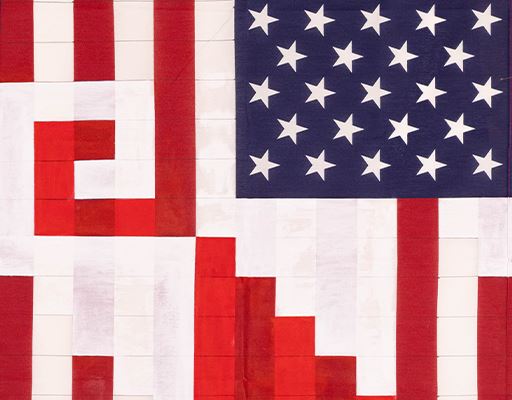

Hüicho! Estamos Unidos, Acrylic on Polyester and Cotton Flag, 60" x 36"

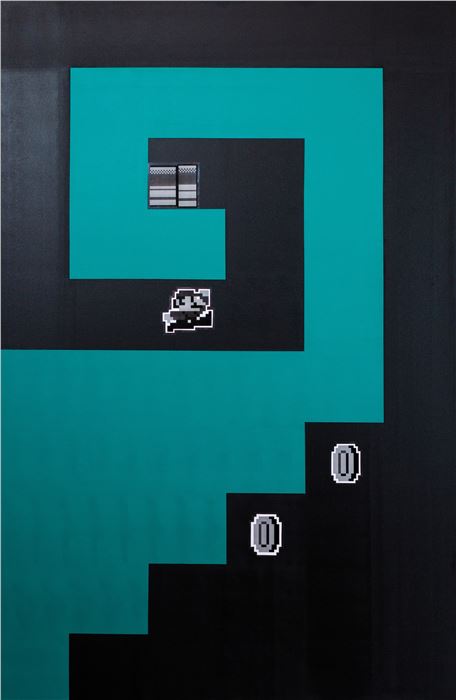

Tying it up with modern technology – the bits, pixels, everything from video games, Tetris, all those shapes, putting those shapes together, like learning that from since you were a kid, putting the digital with the old-school traditional, merging it, living this new life in California, first generation born. There’s a lot of importance. All these shapes have guided us through life.

Hüicho! Mix-tendo, Acrylic paint and laminated paper on canvas, 48" x 72"

Here is his Mix-tendo, which turns the step symbol into a Super Mario pathway set on the 1-2 underworld level, complete with coins and a liminal warp pipe to teleport Mario to another place in the game. This is not a trivialization of his ethnic heritage, this is his lived experience.

Hüicho! Te Has Tejido en Nuestro Corazón, Steel, 30" x 40"

Hüicho! Te Has Tejido en Nuestro Corazón, Steel, 30" x 40"

Hüicho loves the Toyota trucks and cars which have found an iconic status among his people. For his Te has Tejido en Nuestro Corazón (You Have Been Woven into Our Heart) he took the hood of a 1980s Toyota four-by-four, hung it as a panel, and took an angle grinder to it to carve a Mixtec pattern from the steel, literally cutting his heritage into his 21st-century experience – which was made of electronics, cars, and postmodern relativism. “Neon colors bring back a lot of positive thoughts of the eighties,” he said, “I used to look at a lot of magazines. Skateboards, BMX, Kawasaki was always there with all their neon greens, all the neon greens of the eighties. It was popular. And also the glow in the dark. So, I’m putting those together and merging with the ancient.” He is Californian first. He explains,

These are made on canvas, and they’re made on stretcher bars, and they’re made in California, by us, by California people. This is made in the USA. This is me. Down from picking out the wood, to the canvas, to stretching it, to gessoing it, to painting it, to everything. It’s here. This is what it’s all about. Passion. Resiliency. This is what we do. It’s abstract, but it’s very fulfilling inside to know that this is what the art wants me to do, and I’m in service to it right now.

Hüicho! El Regreso, Oil on canvas, 48" x 60"

Hüicho! El Regreso, Oil on canvas, 48" x 60"

Living in the past is impossible, but applying its lessons to the present has offered Hüicho insight and strength to become himself. He is enjoying the abundance and reward of the American Dream. He continued,

I have cousins, they’re the kind of people who made the pyramids, that’s who they are. One thing about this whole immigration and moving process is that we moved and we didn’t have time to think, and I think that’s what the painting also does. It captures a time when I have the time to finally be silent enough to listen to what the art wants me to do and what I want to do, which is to capture a time and place without words, with color and with shape. I’m very happy to be in my situation.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page